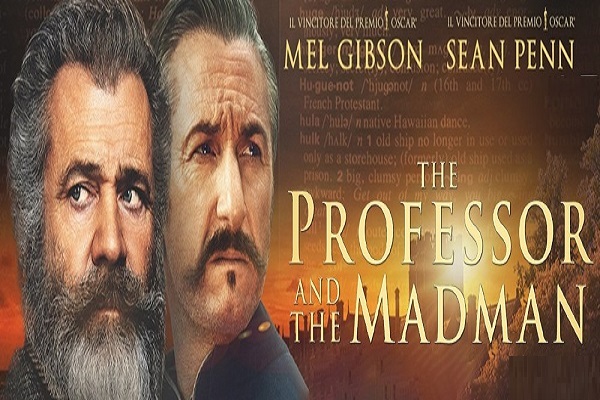

It’s time for a film review. The film has spoken to me and I feel compelled to write about it. Panned by many, praised by others, The Professor and the Madman seems to at least inspire strong opinion. There has been in-fighting, legal battling and disowning. Yet, with all the dysfunction surrounding it, The Professor and the Madman presents as a striking work of art.

I do not hold myself out as a film critic. I occasionally do a book review and I have written a few blog posts on movies, but I don’t claim to know the nuts and bolts of film critique. I’m doing this one because I recently watched it solely because a friend happened to pick it from a Netflix menu and I was moved by it. There’s room for a difference of opinion and I recognize there is probably a more informed basis for film analysis than I have at my off-the-cuff disposal, but I hope to at least make a few valid points in breakdown of the film.

Overview

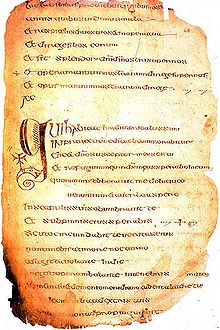

The Professor and the Madman is based on a true life story, centering on the ambitious project by Oxford University Press to create a comprehensive dictionary of the English language, including all the words, all their various definitions and complete etymology. Eventually, it was titled The Oxford English Dictionary. I think of it as the King of Dictionaries.

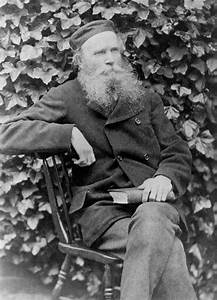

Professor James Murray, played by Mel Gibson, was appointed in 1879 to be the editor of the new dictionary. He is a family man who is now going to be virtually consumed by this lengthy, daunting task of pulling together the complete language from all the people and places where English is spoken and tracing the usages past and present. He is given a small team to work with him. Murray sends a letter to all English speaking countries, asking people to send the Press any words they can contribute on slips of paper. After it becomes painfully clear that the team is far too small and their pace at working through even the “A” section is far too slow, they receive an offer of help from an unlikely volunteer.

William Chester Minor, a former surgeon in the United States Army played by Sean Penn, sends in 1000 slips with words and states he can provide definitions on the most challenging words to properly enter into the dictionary. The most interesting part of Minor’s backstory is that he had been committed to Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum in 1872 for killing a young husband and father who simply answered his door when Minor beat on it. Minor had been running through the streets in terror because he thought he was being pursued by a man who was intent on killing him.

The Thickening Plot

Minor is granted the right to use the library of rare books owned by the asylum’s doctor. He is highly productive in his role of providing complete word entries for the dictionary and is considered a valuable member of Murray’s team as well as a friend. He seems to be making excellent progress mentally as well. He has a guard at the asylum offer his army pension to the widow whose husband he killed in his insanity. Despite her reluctance to accept the pension, bleak prospects for survival for her children and herself make her reconsider. A unique friendship develops between Minor and the widow which takes an unexpected turn.

The Appeal of This Film

On a personal note of minor consequence to many, I started to really enjoy this movie when I saw the work being put into this project by Murray and his team. I have a healthy respect for dictionaries and what goes into a definition. If I had room for the full Oxford English Dictionary, I would own and proudly display one. To watch these dedicated men work their way through the entries, word by word, gave me great joy. It’s a quest worthy of recognition in a film and Murray’s dogged pursuit of a product to be proud of made my respect for him soar.

While I’m mentioning characters, I have to say Minor is one of the most compelling I’ve ever seen. Penn’s portrayal of him is riveting. Gibson turns in one of his best performances as Murray, who appears to be a true professional while also being humble and loving as a father and husband, though overly distracted.

Natalie Dormer as the widow displays more of her depth as an actress. Eddie Marsan plays a familiar role as a person keeping order as a guard, policeman or even as a criminal. He is simply fun to watch and I don’t think I’ll ever tire of him.

The visual quality of this movie is outstanding as well, seemingly true to the period with its grit and simultaneous classy warmth.

Summing it Up

I’m not going into the problems that occurred behind the scenes. It’s unfortunate, but as a viewer I knew nothing of that and I saw it as it was on screen. The quality of this story, the memorable characters with heartfelt performances and the production value prompt me to say it’s the best movie I’ve seen in quite some time. My thanks and respect to all those who contributed what they did and those who refused to do what they didn’t want to do. It all turned out fine from my humble perspective.